Hi. We are Zhan Shi, doctoral student in Policy Studies; Molly Weinburgh, Piper Professor & Andrews Chair of Mathematics & Science Education, Department of Teaching and Learning Sciences; and Daniella Biffi, Data Coordinator at Texas Christian University (TCU) along with Melissa K. Demetrikopoulos, Director of Scientific Communications at Institute for Biomedical Philosophy. We are sharing complexities we encountered studying high-need Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) under NSF Award 2243392 with our team, including Dean Williams at TCU and John Pecore at University of West Florida. The research aims to understand impacts of various learning modalities during the COVID-19 pandemic on STEM teachers’ effectiveness and retention in these districts, and evaluation will determine how research goals are being met.

Lessons Learned

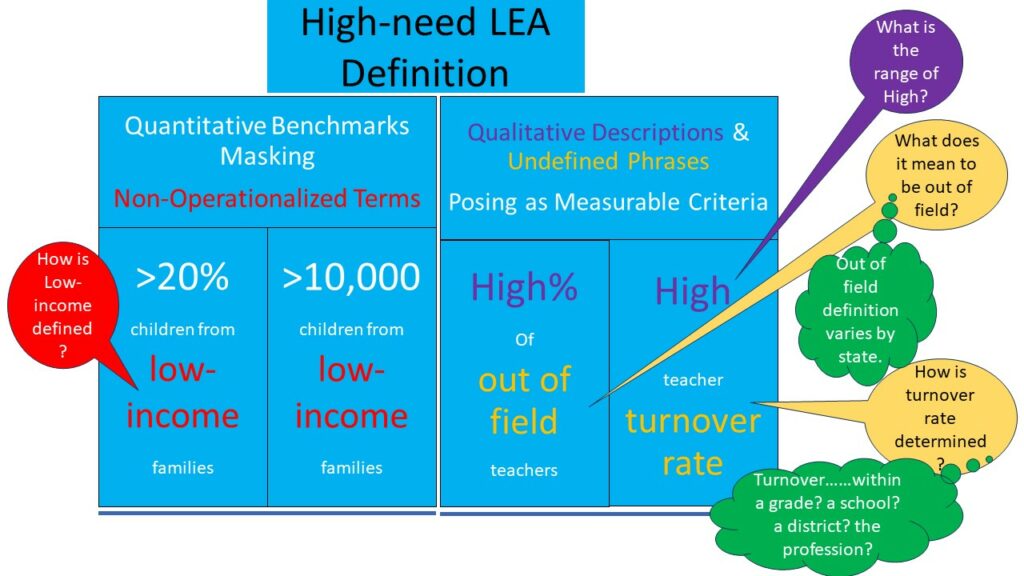

In order to conduct this work, high-need status had to be verified. We attempted to use the definition outlined in section 201 of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA1965) (20 U.S.C. 1021) of a high-need LEA. However, while at first glance the definition appeared well operationalized, much of it was not. For example, criteria dealing with student economic circumstances seemed to be well operationalized with cutoffs like “not less than 20%,” yet “low-income,” a crucial term, was undefined. Luckily, we were able to operationalize low-income to mean “receiving free or reduced lunch” based on the literature and governmental documents. Still, the necessity of deciding how to operationalize terms may ultimately lead to inconsistencies across studies, hindering attempts at meta-analysis or other approaches to compare findings across studies.

More challenging were criteria concerning teachers, which contained un-operationalized terms such as “high percentage,” “not teaching in academic subject areas,” and “high teacher turnover rate.” After conducting an extensive literature review, we found no standard definition of “high” turnover or out-of-field teaching. These definitions vary significantly from state to state and even from district to district. Consequently, attempting to establish a standard measure for these criteria felt like trying to nail Jello to the wall – an impossible task! We even tried to have districts self-identify their status on these factors. However, perhaps not surprisingly, they responded back by requesting benchmarks.

This led us to consider the research purpose and to reconsider the decision to rely upon HEA1965 to verify high-need LEA status. The LEAs were already randomly selected from each US census division, with half selected from those eligible for Title I funding, and the other half selected from districts eligible for other federal programs (Small, Rural School Achievement Program or Rural and Low-Income School Program). This ensured the sample represented different types of communities across the nation, which could be verified for inclusion by measurable student economic circumstances. This shift allowed us to clearly operationalize selection criteria for inclusion while maintaining the research purpose, which was to explore impacts of utilizing different learning modalities during the COVID-19 pandemic on underserved communities.

Hot Tips

While we hope future research and government initiatives will collaborate to establish clearer guidelines for defining “high-need LEAs,” we chose this example to discuss the challenges with operationalizing factors because it initially appeared to be well operationalized and is even codified into law. Evaluation often determines project success in meeting goals, which is impossible if these are not properly operationalized. Goals may include qualitative terms like “increase” or “higher” without clear quantitative benchmarks including percentages, target numbers, and/or comparison/benchmark groups. Furthermore, using terms such as “low-income” or “interest in STEM” without being clearly defined, negates the benefit of other quantified terms. Combinations of quantified limits with undefined terms can mask the lack of operationalized goals and should be clarified before starting a project or more ideally during the proposal stage.

The American Evaluation Association is hosting PreK-12 Ed Eval TIG Week with our colleagues in the PreK-12 Educational Evaluation Topical Interest Group. The contributions all this week to AEA365 come from our PreK-12 Ed Eval TIG members. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this AEA365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the AEA365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an AEA365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to AEA365@eval.org. AEA365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators. The views and opinions expressed on the AEA365 blog are solely those of the original authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the American Evaluation Association, and/or any/all contributors to this site.