Greetings from Vidhya Shanker, independent evaluation consultant and PhD candidate in Evaluation Studies at the University of Minnesota.

Intersectionality is sometimes misunderstood and misused to suggest that oppression based on gender is the same as—or better or worse than—oppression based on race, class, ability status, or other dimensions along which society structures power dynamics. Understanding oppression as interlocking systems, however, revolutionizes mainstream feminism, which is traced to the Suffragette Movement. Today’s blog entry covers intersectionality’s origins, meaning, and applications for evaluators conducting situational analyses.

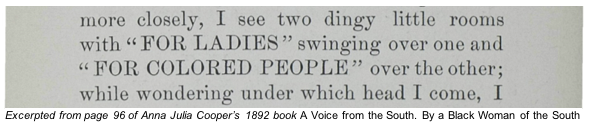

While the experiences and perspectives underlying intersectionality grew from centuries of Black Feminist Thought and indigenous/ postcolonial/ third world feminisms, legal scholar and originator of #SayHerName Kimberlé Crenshaw named and developed the concept in 1989. Crenshaw analyzed the failure of current legal tools to address the discrimination experienced by an African American woman who was denied employment by an automobile plant. The courts said that the plant did employ African Americans—as manual labor; and the plant did employ women—as receptionists. Claiming discrimination on the basis of race and gender simultaneously, they said, was double-dipping.

Prevailing understandings of identity prevented the courts from seeing that all the African Americans employed were men and all the women employed were white. Presumably, the plant considered African American women ill-suited for physical labor because they are women, and ill-suited for public-facing positions because they are African American. Intersectionality would further suggest that the extent to which the plaintiff was perceived as a woman is inherently racialized and the extent to which she was perceived as African American is gendered.

A critical race theorist, Crenshaw was less interested in the defendant’s intent than in the disparate impact of laws that are rooted in constructions of identity as unilateral and fixed. Such understandings allow those experiencing sub-ordination at the intersection of multiple dimensions to fall through the cracks. Crenshaw stated explicitly that intersectionality is not unique to African American women or specific to race and gender.

Hot Tip: Intersectional Situational Analyses

Everyone’s interests are constituted by identification with multiple social groups—we are all sub-ordinated by some systems of oppression and super-ordinated by others. Unlike the phrase “double-minority,” intersectionality conceptualizes identity as greater than the sum of its parts. Intersectional analyses involve examining how sub-ordination and super-ordination play out in a situation along multiple dimensions. For example, how is one’s experience of hetero-patriarchy in a situation inflected by how they are racialized and classed? How one is one’s experience of white supremacy or ableism in a situation inflected by how they are gendered and sexualized? Intersectionality centers the confluence to ensure that those sub-ordinated along multiple dimensions in a situation don’t fall through the cracks.

Look for Parts 2 and 3 for Intersectionality in Program Theory and Evaluation, respectively.

Rad Resource: Rinku Sen’s How to Do Intersectionality discusses intersectional analyses in movement organizing.

The American Evaluation Association is celebrating Feminist Issues in Evaluation (FIE) TIG Week with our colleagues in the FIE Topical Interest Group. The contributions all this week to aea365 come from our FIE TIG members. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this aea365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the aea365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an aea365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to aea365@eval.org. aea365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators.

Pingback: FIE TIG Week: Applying Intersectionality to Program Theory: Gender-Based Violence & Violence Against Women by Vidhya Shanker – AEA365