Vidhya Shanker here, from Rainbow Research. Previously, I explained intersectionality—despite cooptation by contemporary organizations vying for funding—as a centuries-old concept borne from subjugated knowledge and liberation struggles as valuable for situation analyses. Today, I examine intersectionality’s value in relation to certain dimensions of program theory.

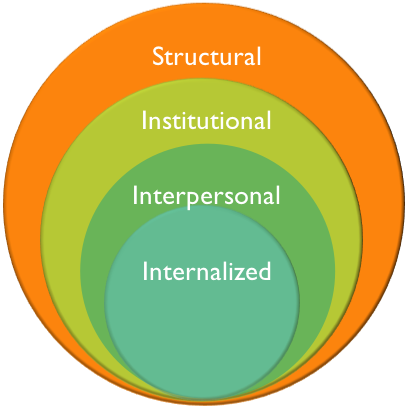

Lessons Learned: Before becoming an evaluator, I spent years fighting domestic violence. I was privileged to work with the originator of the Power & Control Wheel, which initially linked nested levels of violence. It has since been reduced to dynamics within (internalized) and between (interpersonal) individuals.

While most victims/ survivors of intimate partner violence identify as women and most of those who exercise violence identify as men, programs theorizing such violence as an issue of gender alone obscure differences within the category of “woman.” Experiencing sub-ordination as a woman does not preclude women from internalizing super-ordination along other dimensions of identity. Focusing exclusively on gender dynamics also obscures shared experiences of sub-ordination between women and men in indigenous, immigrant/ refugee, and queer communities as well as communities of color and people with disabilities—failing those communities. Indigenous women, in particular, inhabit a jurisdictional “no-woman’s land” in terms of the interpersonal violence perpetrated against them by white assailants and structural violence inherent in settler-colonial governments’ protection of those assailants.

(This post includes hyperlinks to some pivotal texts that have

developed the notion of intersectionality)

Honoring complexity among, between, and within categories, intersectionality asks, “How are both women and men’s experiences of violence shaped by structural patriarchy intersectionally with other structures of oppression such as white supremacy, economic exploitation, heteronormativity, transphobia, ableism, xenophobia, and militarism?” It offers us opportunities to theorize and evaluate programs expansively—accounting for history, context, and power—rather than reductively.

Theorizing Programs with an Intersectional Lens to Fight Gender Based Violence & Violence Against Women

In 1972, mainstream feminists organized responses to domestic violence rooted in hotlines, shelters, social services, and the justice system’s recognition of domestic violence as criminal. In 1991, Kimberlé Crenshaw analyzed how hotlines and shelters reflect the languages, family sizes/ structures, parenting styles, and dietary habits of straight, white, middle-class cis-women. Additionally, underlying these mainstream programs are the assumption that all women feel safe with law enforcement and the theory that incarceration ends the violence that women experience. Instead of ending the violence experienced by women from marginalized groups—who often have legitimate fears of law enforcement—incarceration, deportation, and death at the hands of law enforcement exacerbate the violence that marginalized women experience interpersonally, in their communities, by the state, and through war.

Rad Resources:

Most constituent-led programs that theorize intimate partner violence as sub-ordination along multiple levels and dimensions (beyond interpersonal misogyny) and respond accordingly are unfunded and invisible. Examples include:

- Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective

- Creative Interventions

- There is No “We”: V-Day, Indigenous Women and the Myth of Shared Gender Oppression

Links to the books:

- https://combaheerivercollective.weebly.com/the-combahee-river-collective-statement.html

- https://www.feministpress.org/books-a-m/but-some

- http://www.sunypress.edu/p-6102-this-bridge-called-my-back-four.aspx

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Making_Face_Making_Soul_Haciendo_Caras.html?id=jJAnAQAAMAAJ

- soniashah.com/books/dragon-ladies/

- https://books.google.es/books/about/Colonize_This.html?id=tCZQo3aHhpIC&redir_esc=y

- http://www.agenda.org.za/

- https://books.google.es/books/about/Indigenous_Women_s_Writing_and_the_Cultu.html?id=eGgkDwAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

The American Evaluation Association is celebrating Feminist Issues in Evaluation (FIE) TIG Week with our colleagues in the FIE Topical Interest Group. The contributions all this week to aea365 come from our FIE TIG members. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this aea365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the aea365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an aea365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to aea365@eval.org. aea365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators.

Thanks, Alexis!

Sorry for the delayed reply. I’m afraid I am unfortunately not usually available a day or two at this stage of life–and that’s likely true of most people. This is especially so now as my partner and I perform the INVISIBLE (REPRODUCTIVE) LABOR of attempting to raise our child and homeschool her–doing the work of two groups (mothers and teachers) most undervalued by capitalism and patriarchy, which ensures the future of humanity–while we also do the work that allows us to have a roof over our heads today. I’m more fortunate than most in that all three are usually life-giving even if sometimes draining. The same is true of engaging in the INVISIBLE (RELATIONAL) LABOR of talking with emerging evaluators: I usually find it life-giving, even if sometimes draining. I just need more notice, please. You should be able to find my contact information through AEA’s website–that is probably a better channel of communication than this public forum.

Thanks again,

Vidhya

Hi Vidhya,

My name is Alexis and I am a Master of Public Health student at the University of Arizona. For one of my courses we were assigned to find and interview a program evaluator in a topic of interest to us. I’ve read a couple of your posts now and I would like to email/call/Zoom with you today or tomorrow, if possible. The interview will be short and mostly give you a platform to discuss what it’s like to be an evaluator, the challenges, and why it is important.

Best,

Alexis