My name is Julia Coffman and I am Director of the Center for Evaluation Innovation, a nonprofit effort that is building the field of evaluation in hard-to-measure areas such as advocacy, communications, and systems change. I am also a strategy and evaluation consultant to nonprofits and foundations, specializing in advocacy and policy change efforts.

Advocacy to advance public policy can be a powerful way to achieve large-scale and lasting results for individuals and communities. But sometimes a mismatch occurs between public policy goals and the strategies chosen to advance them. For example, we know awareness alone typically doesn’t drive policy change, but how many public awareness campaigns have been funded with the expectation that they alone will drive policy? Before specific tactics are chosen, several important decisions must be made.

Hot Tip: Follow these five steps when developing a public policy strategy:

- Choose the public policy goal: Select ambitious goals, but make sure they follow the SMART rules (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, timely).

- Understand the challenge: Assess where issues of interest currently stand in the policy process, along with why they are stuck.

- Identify which audiences can move the issue: Determine who to engage to address the barriers identified in the last step. Audiences may include the public (specific segments of it), policy influencers (politically-influential individuals or groups), or decision makers.

- Determine how far audiences must move: Assess where audiences currently are in terms of their engagement, as well as how far they need to move in order to achieve policy success. Audiences may be completely unaware that problems exist. Alternatively, they might be aware that problems exist, but do not see them as important enough to warrant action. Or, even if the willingness to act exists, audiences may not have the necessary skills to advocate.

- Establish what it will take to move audiences forward: Identify the strategies and activities that will move audiences and support effective change.

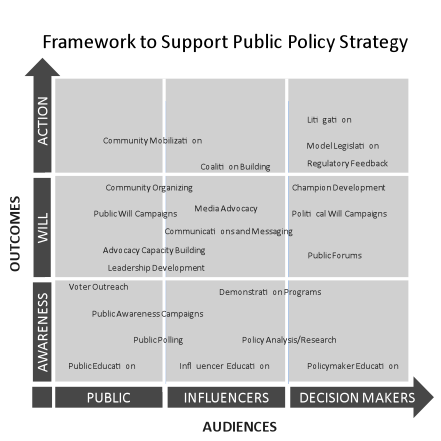

Rad Resource: This visual framework was developed to support steps 3, 4, and 5 above. The framework contains specific types of strategies and activities, organized according to where they fall on two strategic dimensions—the audience targeted (x-axis) and the outcomes desired for those audiences (y-axis). The framework forces the consideration of audiences and outcomes before tactics are chosen.

Rad Resource: Read more about this framework and its application in the 2009 article I wrote with Martha Campbell in The Foundation Review. http://www.innonet.org/client_docs/File/center_pubs/public_policy_grantmaking.pdf

This contribution is from the aea365 Daily Tips blog, by and for evaluators, from the American Evaluation Association. Please consider contributing – send a note of interest to aea365@eval.org.

Hola Ricardo! What a pleasure to hear from you again. Thank you so much for your very thoughtful comment in response to my post.

I completely understand and agree with what you are saying about the uncertainty of the public policy arena and the fact that advocacy efforts almost always evolve and change over time (as do their evaluations). What I didn’t say next to that first step is that I always advise the advocates or organizations that I work with to be prepared for the fact that their goal may need to shift over time. In fact, we often go through an exercise of thinking through the conditions under which such a shift might need to occur. For example, some advocates want to create “contingency logic models” because they expect certain political or economic shifts to occur (e.g., elections), and they want to be prepared if they do. I’ve used another exercise called “advocacy premortems,” in which we assume the advocacy effort they are planning has failed completely. The advocates then identify all of the risks or things that could go wrong with it so both they and the evaluators know what to look out for in the future. This helps to address the concern about putting blinders on and being prepared for the unexpected.

I still do, however, ask for precise goals upfront because I have seen the danger of doing the opposite. In my experience, being unclear about the policy goal typically means being unclear about the strategy needed to get there. It also leads to the lack of a clear advocacy “ask.” And, in my opinion, that can be more counterproductive than trying to develop a goal under uncertain conditions.

Thank you again for your comment, Ricardo. As always, you’ve made me think.

Warm regards,

Julia

Hola Julia,

I speak as someone who spent some thirteen years working to influence public policy decision-makers as a journalist and then environmental campaigner, and now for the past seven years as an evaluator of the outcomes of public policy advocacy initiatives.

All five steps except the first one resonate with that experience. I do not think that I can remember a case when SMARTly defined goals where the results that actually eneded up being achieved. The arena of public advocacy is rife with complexity – the cause and effect relationships between what you will do and what you will achieve are simply unknown. In fact, defining what you want to achieve so precisely is usually counterproductive, because of the waste time and resources in attempting to predict the unpredicatable, or because of the blinders you set for seeing the unexpected, or the discouragung disappointment of not achieving what is so meticulously planned.

Best wishes,

Ricardo