Hello again! It’s Antony, Veronica, and Vidhya back to consider what an expanded and deepened idea of harm and healing means in practice for the integration of technology into evaluation.

In much of our work, tools such as information systems, mobile data, biometric registration, and digital dashboards are increasingly used to collect, identify, and track recipients.

Digital and evaluative risks

As technology evolves, we expect to see tools on learning, decision-making, and intelligence programs to assess performance. These developments amplify potential harm to people and pose several risks that evaluators should consider in their work. Building from previous posts exploring decolonization and ethical dimensions of evaluation, we discuss a few risks below and provide tips and resources for evaluators to learn more.

Risk #1: Decontextualization & Dependence: Many technological solutions applied through development assistance are exogenous to local communities’ needs, norms, and values. As such, they exacerbate the effects of exclusion, marginalization, and infantilization. Rather than building from local contexts and amplifying indigenous solutions, they reinforce a dynamic in which colonized groups are dependent on colonial powers.

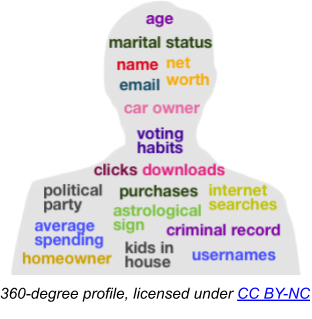

Risk #2: Individualism & Consumption: These interventions are usually framed around users as individual agents, whose access to technology will allow them to control their destiny, instead of being framed around the collective practice of decolonizing, grassroots data science and data sovereignty to repair the harms of economic, political, and cultural imperialism. Data sovereignty means that the people whose data are being collected—and who can potentially be harmed by their use—determine the purpose and process of their collection, analysis, interpretation, and application.

Risk #3: Security & Privacy: These solutions compromise digital privacy by generating personal and sensitive data and metadata that can map private individual behavioral patterns. Surveillance capitalism describes the involuntary exchange of control and ownership of personal data for connectedness. In development and humanitarian settings, people are expected to hand over data, for example their biometric data, in exchange for support services and other benefits.

Hot Tips: What can evaluators do?

Tip #1: Evaluators can direct attention to the flow of knowledge and technology. For example, we can identify interventions that are one-way, depositing outside knowledge and technology into local communities or extracting local knowledge and technology to serve outside as opposed to local interests.

Tip #2: Evaluators can support digital decolonization, data sovereignty and data ethics efforts by amplifying cycles of knowledge and technology production, consumption, and transformation that are reciprocal and potentially healing. See here to learn more about the rise of data ethics.

Tip #3: Evaluators can distinguish among the types of value that data can produce, and for whom. These types range from accumulative and competitive value generated through surveillance capitalism to instrumental, educational, cultural, and spiritual value generated through grassroots data science.

Rad Resources

- Animikii contextualizes digital decolonization and data sovereignty through indigenous technologies.

- Advocacy organizations halted data-sharing among a school district, city, and county.

- The Coalition of Asian American Leaders helped pass the All Kids Count Act to disaggregate student data in ways that serve minoritized groups’ interests.

Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this aea365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the aea365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an aea365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to aea365@eval.org. aea365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators.

Great post. Cloud-based services like Amazon Web Services, Azure, IBM Cloud and Google Cloud have enabled companies to deliver software products and services on a global level, allowing quick access to computing power, storage, databases, and advanced technologies such as machine learning, data lakes and analytics.

Yes, and our ethical concern is that these typically come at the cost of local communities’ autonomy, knowledge, and privacy–reinforcing existing inequities and putting people at risk of surveillance and violence. Grassroots data science, in contrast, is locally-led and serves communities’ interests rather than corporate interests in new markets.

Thanks for reading/ writing.