We are Francesca D’Emidio, Liisa Kytola, and Sarah Henon from ActionAid, and Eva Otero from Leitmotiv consultants. ActionAid is a global federation working to achieve social justice and poverty eradication by transforming unequal gendered power relations. We’d like to share an evaluation methodology tested in Cambodia, Rwanda, and Guatemala to measure shifts in power in favour of women.

Our aim was to empower women from very disadvantaged backgrounds to collect and analyse data to improve their situation. This is in line with our understanding of feminist evaluation, where women are active agents of change. Our evaluation sought to understand any changes in gendered power relations, how these changes happened, and our contribution.

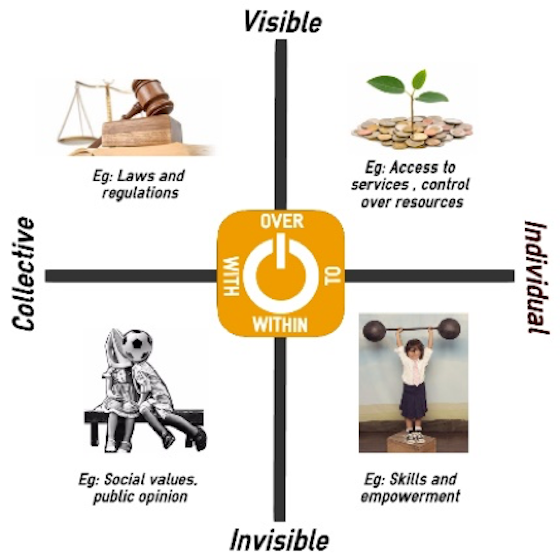

To start, we developed an analytical framework based on four dimensions of power, inspired by the Gender at Work framework and the Power Cube.

We then trained women leaders of collectives to use participatory tools and facilitate discussions. Leaders then identified factors that describe people with power. After this, leaders facilitated discussions with collective members, drawing community maps to identify important spaces (home, market etc.). Using seeds women scored spaces where they currently had most power and then repeated the exercise for the past to understand what had changed. Women then told stories in groups to explore how they gained power in these spaces. We mapped the changes experienced by women against the dimensions of power and analysed findings with leaders. Timelines were used to understand our contribution. Finally, we triangulated the information by interviewing other stakeholders.

Lessons learned:

- Our methodology makes power analysis simple, concrete, and rooted in contextual realities, enabling women who are illiterate to lead and participate in the process. Women quickly grasped the concepts and confidently facilitated conversations, finding the process empowering.

- Women need to define power in their own context. We asked women to name the most powerful people in their communities to identify “factors of power.” This allowed us to understand how participants viewed power rather than imposing our own frameworks on them.

- Designing a fully participatory evaluation process can be challenging. A shortcoming was that women did not design the evaluation questions with us. Women found analysis tiring after a long data collection process. We need to better balance women’s active participation with their other responsibilities and logistical challenges.

Hot tips:

- Use role play to bring abstract concepts to life. We asked groups to organise plays to represent different dimensions of power.

- Let local people own the space. The more freedom they have, the more they are likely to get to the root of the issue by talking to each other, rather than to ActionAid. We overcame the challenge of documentation by hiring local women as note takers.

The American Evaluation Association is celebrating Feminist Issues in Evaluation (FIE) TIG Week with our colleagues in the FIE Topical Interest Group. The contributions all this week to aea365 come from our FIE TIG members. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this aea365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the aea365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an aea365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to aea365@eval.org. aea365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators.

“Letting local people own the space” hardly seems feminist. They DO own the space, and they can do more than note-take. They can lead. More often than not, they already had their own initiatives addressing gender-related issues (and gender-related issues may not even have presented themselves the way they do now before colonization and capitalist “development” and neoliberal austerity measures imposed by the IMF and World Bank).

The question is really whether they let Action Aid and the evaluators in to their space–were they ever asked?

This sounds like a really inclusive and participatory evaluation method. Before reading this article, I had never thought about evaluation methods and literacy. The methods outlined in this article are accessible and, more importantly, do not impose on those being evaluated. I think it’s very important, especially when talking about power imbalances, that there are not power inequities in the evaluation methods.

By prompting the women in different ways like role-play, the evaluation becomes less threatening. I strongly believe art and creativity cross barriers that no other form of communication can cross. Art allows us to let our guard down and engage with topics that may be too difficult to talk about.

Hello Francesca, Liisa, Sarah, and Eva,

I am a student pursuing my master of education degree through Queen’s University. I am in a course about program inquiry and evaluation. My most recent assignment was to find a blog post on the AEA website that interested me and provide a response to the author(s). I didn’t have to look long before finding your post: Feminist Issues in Evaluation TIG Week: Participatory methods enable women to analyse shifts in power (posted by Liz Zadnik. Your evaluation methodology to measure shifts of power in favour of women caught my eye. ActionAid is an inspirational program. I had not heard of it before reading this post. I visited your website and watched your ‘Theory of Change’ video. This gave me a good understanding of your mission and specific goals. Reading about how you used program evaluation with the Action Aid program was a really grounding experience for me. It helped me connect what I have been learning about in class with a real world example of how program evaluation can contribute to really positive social changes. The purpose of your evaluation – to understand changes in global power relations, how they happened, and how ActionAid contributed – will contribute greatly to the success of ActionAid. Collecting and analyzing information to improve the situation of thousands (if not millions) of impoverished woman, is an inspirational example of how to use program evaluation. One thing that particularly stood out to me concerning the program evaluation was the precautions you took to ensure that you did not impose your own bias or values on the women participants. Having they define power and facilitate discussions, and take notes, were methods I will note to help get to the root of the issues by talking with each other rather than with the evaluator.

I think your program is grounded in strong principals that truly are needed to work toward solving the problem of gender inequality and poverty. Thank you for sharing the role program evaluation plays in achieving your goal. It really did round out my understanding of and appreciation for program inquiry and evaluation.

Sincerely,

Kali Sinden

Great work.

I studied power in university, including Feminist and Aboriginal ideas. Before reading up on those perspective’s I had a sense that there had to be power that wasn’t just “power over,” and tried to argue for that with a Marxist professor, but lacked the effective language until I came across Feminist and Aboriginal perspectives.

“Power with” is so critical. The examples you use in the diagram do not include Friendship/kinship relations. I wonder if you included them in your framework?

Loving and caring for others, and creating bonds where others love and care for you is a strong form of power. It helps to have others use their power for you because they care for you; rather than because you have power over them.

Hello Paul, I am interested in finding out how you analysed “power with” or “power within”. I agree with you that friendship, kinship, family of societal relationships are a vital component of power that needs to analysed carefully especially from the angle of -how the power is used or exhibited to the benefits of the poor and vulnerable members of the society.