Greetings! I am Beverly Peters, an assistant professor of Measurement and Evaluation at American University. This is the fourth article in a 5 part series on Using Interviews for Monitoring and Evaluation. In the previous article of this series, we discussed different sampling strategies that evaluators might employ when deciding who to interview.

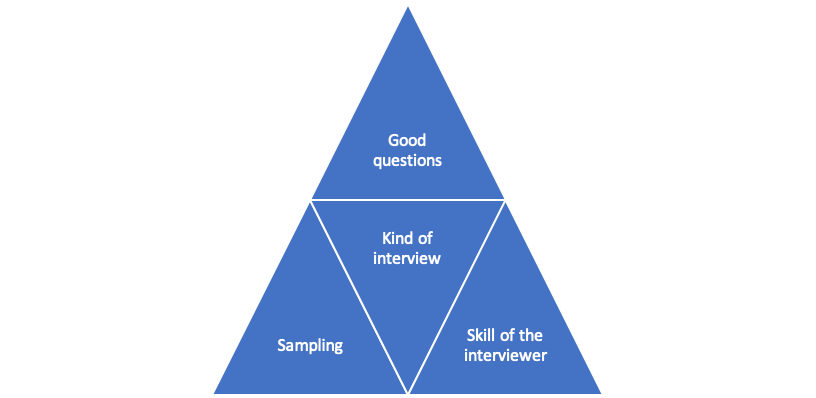

So far in this series, we have learned that choosing the right kind of interview and sampling strategy help to set the foundation for your interviews. Equally as important for collecting useful data from interviews are developing good questions, and having the skills to conduct interviews that will ultimately gather the rich, emic data we need as qualitative evaluators.

An important first step is crafting open ended, easily understood questions that help to illicit conversation and gather the rich emic data that is so important for us as qualitative evaluators. Good qualitative questions yield rich, descriptive data, and often ask about issues that are puzzling or problematic. You will likely find that you are able to craft more meaningful, informed questions if you have some knowledge about the project and the population.

As you develop your interview guide, you should organize your topics logically, asking an open ended or grand tour question first, to set your respondent at ease and get the conversation started. A grand tour question also gives the respondent a chance to tell you what they think is important. Ease your respondent into more controversial or sensitive questions towards the middle of the interview, after you have already developed rapport and trust.

As you craft questions, remember that you need to use wording and language that will make sense to your respondent. Likewise, your questions should not be confusing or overly controversial or accusatory. Evaluators always pilot their interview questions to learn what questions are confusing and need rewording, which questions yield useless data, and what additional questions need to be added to the interview guide.

Good qualitative interviewing requires us to have technical skills—how to develop a good interview guide, how to develop a good interview question, how to ask sensitive questions, and how to get more information when your respondent is not forthcoming with insight that you need for your evaluation design. You need to be able to read body language, and pinpoint areas for follow up. You need to be able to understand the local or project culture and be able to craft questions that are appropriate.

Good qualitative research, and good qualitative interviews, also require us to build rapport. In addition to discussing confidentiality with your respondent, this relates to being patient, tolerant, and perhaps even being humorous. Being a good interviewer also means being a good communicator, and being cognizant of who you are as an individual. Language and cross cultural communication skills can also help us to build better rapport with our respondents.

Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this aea365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the aea365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an aea365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to aea365@eval.org. aea365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators.

My name is Nancy Milton and I am a Professional Masters of Education student at Queen’s University. I am currently enrolled in the Program Evaluation 802 course for which I am working on a design plan that will evaluate a high school literacy intervention program. I am very new to evaluation, having no background knowledge or experience in the field whatsoever, and am feeling a bit in over my head! I came across your article while searching for posts that would enlighten me on quality interviewing as a qualitative research method, and you did not disappoint!

I have learned that there is a lot more to interviewing than I initially thought.

You mentioned that interviewers need to be good communicators in order to establish rapport with participants, and I couldn’t agree more. Afterall, we are all human, and we instinctively respond more willingly and honestly to someone who is “patient, tolerant, and perhaps even humorous.” I’m sure all trained evaluators have these capabilities, but with different personality types out there, I expect these traits would come easier to some than others.

I appreciated tips like the importance of piloting your interview questions to determine in advance which ones come across as confusing and need re-wording, to easing the respondent into more controversial or sensitive questions towards the middle of the interview, after you have already developed rapport and trust through more open-ended “grand tour” questions. Even the importance of knowing the “local or project culture” to developing meaninging, insightful questions in valuable information to a newbee like me. I can see now why gaining a strong sense of the context in which a program is being implemented is imperative to effective program evaluation; this point was definitely driven home by my course instructor as we began our program evaluation design plans.

Another tip I found particularly helpful was that in order to yield rich, descriptive qualitative data, evaluators need to ask open-ended questions about issues that are “puzzling or problematic,” and based on intuitively judging body language, be able to pinpoint areas for follow-up. The numbers associated with quantitative data simply cannot reveal this kind of valuable information.

I wonder if many evaluators have been engaging in program evaluation interviews through tele-conferencing platforms like Zoom during the Covid-19 pandemic, and if so, what limitations this has imposed. Perhaps there are benefits? You mention the importance of having strong communication skills, and being able to read respondents’ body language and gestures; I find this much more difficult to do through a computer screen, and I wonder if skilled evaluators think the same.

Learning about the many skilled traits of an effective interviewer reminds me just how diverse and demanding the role of program evaluators is: we really do wear quite a collection of hats with all the different areas of expertise we are expected to have! I have recently read 2 articles published decades ago by Shuhla & Cousins (1997) and Weiss (1998) that make this very point: with the rise in use of collaborative models comes greater demands on the evaluator– the evaluator’s role expands from data-collector (ie. interviewer) to program planner, educator/trainer, agent, consultant, and advisor to organizations and programs. I wonder (anxiously) if, 20+ years later, these roles continue to expand?

Thanks so much for sharing all your practical, helpful tips on how to collect quality, quantitative data through interviewing!

Nancy Milton

Shulha, L., & Cousins, B. (1997). Evaluation use: Theory, research and practice since 1986. Evaluation Practice, 18, 195-208.

Weiss, C. H. (1998). Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluation? American Journal of Evaluation, 19, 21-33.

Hi Beverly,

I completely agree that it is important to research the program and population. Social programs are literally designed to try to meet the needs of the population, whatever they may be. Different groups of people from different places with different cultures and the like will respond differently but may also need different programming to help with the same issue as another population. I didn’t realize how important building a rapport with the participant of a program is to an interview for an evaluation of that program. I am currently in a course teaching me about program evaluation and the example program I have been using is an educational program. But now that you mention relationship-building in the context of gathering data, I realize that there are some programs that would require much more personal information or feelings to be discussed than my educational program would. Participants may not feel comfortable talking about these things during the program that is being delivered by a facilitator they know, much less during an evaluation of the program by a stranger. I appreciate the advice to start with softball questions to build that rapport before diving into deep or controversial questions.

I appreciate the tips for interviewing you gave us, such as starting off with a broad question not just so the participant will feel more comfortable but also so you can get a sense of what is important to them. I also think it is very important that there is a piloting stage where the questions are tested for things like clarity and relevance. I am wondering exactly how that works. For example, will you have sample interviews with real participants who will then be re-asked the final versions of the questions, or would you ask other program evaluators or other stakeholders in the program?

Thank you,

Laura.

Thank you for your post on collecting data from interviews. I found this to relate a lot to your article on the interviewing continuum as it helps describe how to move towards a semi-structured and unstructured interview properly.

I appreciate your guide of using an open-ended question at the beginning of the interview to allow the respondent to take control of the interview hopefully helping to put them at ease. Afterwards, once rapport has been developed, more difficult questions should be asked in the middle of the interview. My question for you is there a specific way to end the interview? Are you looking to end with more open-ended questions or less controversial questions to put the control back with the respondent and end on a good note for rapport?

It is clear from your article the amount you value rapport and see similarities between an interviewer and an educator requiring patience, tolerance, reading body language, and using humour to increase effectiveness.

One part of your article which surprised me (although it makes perfect sense) is that evaluators always pilot their interview questions. I was wondering if you could elaborate a little more about how that logistically would work within the framework of an evaluation. Time and access to respondents must factor in. Is it more your interview questions evolve throughout the process or would that affect the accuracy of your data from the different respondents?

Thanks for your series on interviews,

Zac