Justin Laing is the principal of Hillombo LLC, a capital and race critical strategy, research, planning, and evaluation consultancy rooted in Black Studies.

Recently, I’ve been thinking that the justness and criticality of my evaluation or reflection work is related to my consideration of the dominating histories of “culture” in Western Europe and the U.S. I have been persuaded by the argument of Raymond Williams, in “Culture and Society: 1780-1950,” that “culture,” as it exists today in the name of philanthropic “arts and culture” programs, originated in the 18th and 19th centuries as a strategy of capitalist reform and perpetuation. Worsening matters, Williams’ case for “culture as reform” connects well with Dylan Rodriguez’s argument that reform is a strategy of counterinsurgency.

Williams argues it was a movement of English writers, critics, and politicos, including Edmund Burke and Matthew Arnold, that furthered capitalism’s exploitation of the English working class, itself standing on the morally bankrupt and humanly incomplete process of exploiting, robbing, enslaving, and murdering Africans and the peoples indigenous to the Americas, what Karl Marx called capitalism’s phase of “primitive accumulation.” The movement was to create a particular framework of “culture” intended to steer the English working class towards cleaning up their poor and wretched lives through comportment and high mindedness (and Eurocentricity) rather than organizing as a class to address the terrible work and living conditions of the “industrial revolution” (or act in solidarity with African and peoples indigenous to the Americas whose exploitation was the very basis of the industrial revolution). This process then migrated to the museums, orchestra halls, and theaters of the U.S. to shape these institutions as places to discipline the White working class to attend the museum, speak in hushed tones, get inculcated with the European Supremacist theory of aesthetics, and, once again, deepen their commitment to standing with the European capital classes as settlers.

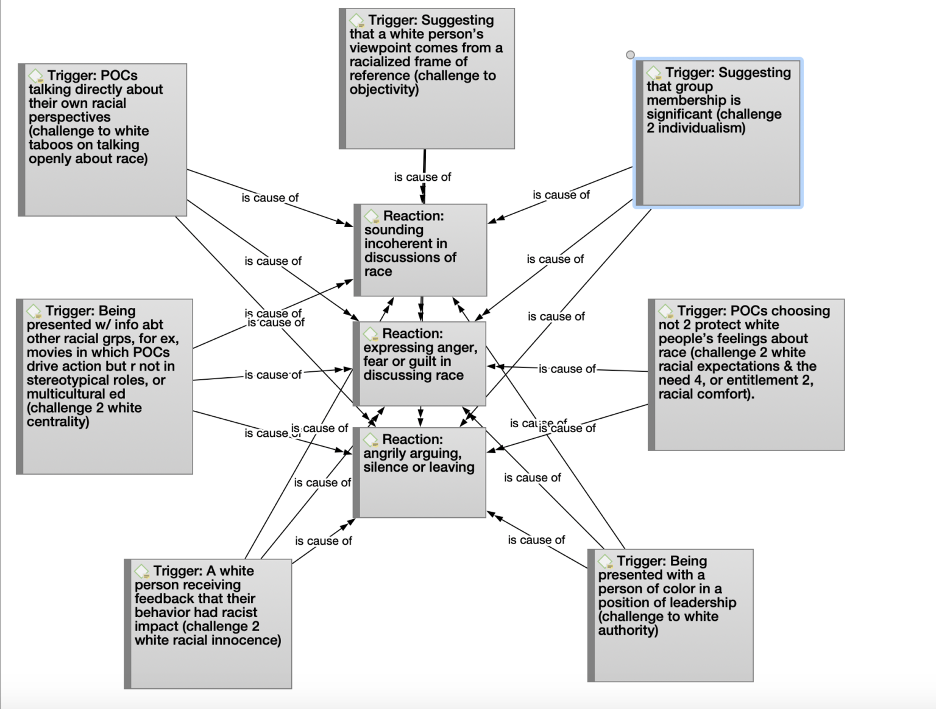

Today, “culture,” as a strategy of public or privately funded “arts and culture” programs, seems to me to bear the marks of the objectives for which it was birthed. What feels different today is that because of the civil rights and liberational struggles to which DEI was offered as an “answer”, the people who have access to participate and uphold the banner of “culture” is now multi-racial. This is a difference since in the era Williams is describing when culture first emerged, “aesthetics”, to which culture is deeply related, was an explicitly European Supremacist framework. All of this leads me to agree that DEI is better understood as tactics of neocolonialism. In this process, the professional strata of the “formerly” colonized, i.e. BIPOC, are recruited to manage and embody the potential for reform but the contradictions are signaled in the lack of inclusion. This contradiction is gestured to in this mapping I did (see below) of a DEI arts program and the White bullying/fragility that appeared as “bullets” in response the “triggers” of BIPOC self-assertion.

Thinking of DEI as a strategy of counterinsurgency would lead to me to say the indicators above show DEI to be “working.”

Hot Tips

Consider designing questions to explore with participants the political outcomes and social relations that the program is helping to bring about and obscure. In other words, challenge culture’s claim to being an innocent, apolitical bystander to the ugliness and cruelty of “the world” i.e. racial capitalism.

Rad Resources

In addition to Williams, consider complementing your theoretical framework and assumptions with:

- Marimba Ani’s “Yurugu: An Afrikan Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior”;

- Oyeronke Oyewumi’s “The Invention of Women: Making An African Sense of Western Gender Discourses”

- Rizvana Bradley’s “Anteaesthetics: Black Aestheis and the Critique of Form”; and

- The Critical Theory Workshop, Afro Pessimist & other approaches that read culture “against the grain.”

The American Evaluation Association is hosting Arts, Culture, and Museums (ACM) TIG Week. The contributions all week come from ACM TIG members. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this AEA365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the AEA365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an AEA365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to AEA365@eval.org. AEA365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators. The views and opinions expressed on the AEA365 blog are solely those of the original authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the American Evaluation Association, and/or any/all contributors to this site.