Kia ora from Aotearoa, New Zealand. Our names are Maria Hepi and Jeff Foote and we are part of a cross-cultural research and evaluation team from the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, Universities of Otago and Canterbury and Victoria University of Wellington. Over several years, we have undertaken research in partnership with Hokianga based M?ori indigenous researchers from a community owned health service and hap? (subtribes) in Aotearoa New Zealand, on how community development can address environmental health issues.

Lessons Learned

A critical issue in undertaking a systemic inquiry with an indigenous community is ensuring that the values and interests of that community are not unwittingly marginalised by the uncritical application of evaluation methods. As systems thinkers such as Werner Ulrich and Gerald Midgley remind us, all inquiries are partial and are shaped by ingrained assumptions and values. As evaluators we must carefully reflect on whose expertise is privileged in decisions about who is considered an ‘expert’, what ‘expertise’ counts and what will ‘guarantee’ a successful inquiry (e.g., cultural competency of the evaluation team).

Our experience is that being critical about boundaries – what or who is included or excluded – is essential to framing systemic inquiries in ways that reflect Hokianga hap? aspirations, interests and values. We found that ongoing discussion about boundaries led to an understanding of the evaluand that encompassed indigenous values and identified outcomes from an indigenous perspective. This was important to ensure our evaluation was firmly grounded in an indigenous worldview and avoided deficit framings.

An example of how we applied boundary critique

The New Zealand Ministry of Health (MoH) undertook a safe drinking water pilot project with Hokianga hap?. Specifically, the pilot project looked at if it was cost effective to provide safe drinking water to marae (a focal point of in a M?ori indigenous village). The MoH’s evaluation of the pilot project drew narrow boundaries and focused on whether the risk from waterborne illness had decreased. In doing so it missed significant cultural and social benefits for the hap? participants. Hokianga hap? dismissed the evaluation as culturally non-responsive and sought assistance from our cross-cultural evaluation team who adopted a wider boundary around the evauland to document ‘spill-over’ outcomes such as how hap? used the project pilot to create employment and fulfil guardianship responsibilities over the water ways.

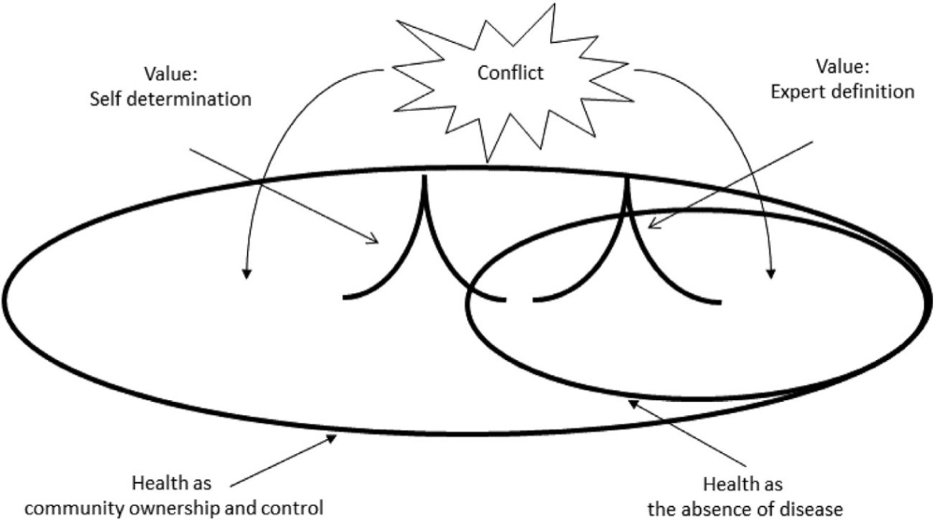

Figure 1 sets out the tension between these two boundaries. Prioritising the physical dimensions of health created a primary boundary around which the safe drinking water pilot was understood. A second and broader boundary, which includes the MoH’s concern for safe drinking water, captures a more expansive understanding of health in terms of community ownership and control. Hap? views were at risk of being marginalised by the Ministry of Health’s environmental health framing. We recognised that hap? expertise was central to understanding how hap? engaged with the safe drinking water pilot project and created benefits beyond safe drinking water. Our systemic inquiry was firmly rooted in the M?ori indigenous worldview.

For further reading on using boundary critique in cross-cultural evaluation you can read our recently published article here.

The American Evaluation Association is hosting Systems- and Complexity-informed Evaluation Week. The contributions to AEA365 this week are all related to this theme. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this AEA365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the AEA365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an AEA365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to AEA365@eval.org. AEA365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators. The views and opinions expressed on the AEA365 blog are solely those of the original authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of the American Evaluation Association, and/or any/all contributors to this site.

Great post!

I love this: “all inquiries are partial and are shaped by ingrained assumptions and values”

And also that “…a more expansive understanding of health in terms of community ownership and control.”

Thanks